Railcar 50 Display Boards

1 - Introduction

2 - Pre-DMU Days

3 - Early Thinking, Plans

4 - The Early Types

5 - The Modernisation Plan

6 - Service Improvements

7 - A Wide Variety of Vehicles

8 - Refurbishment and Replacement

9 - Preservation - the early days

10 - Preservation - the HLF Projects

11 - Preservation Now

12 - Credits

The Railcar50 event at the Severn Valley Railway in October 2004 featured many visiting vehicles. Many of these were in traffic, some were on static display at Bewdley. Other displays included mechanical components and a set of display boards which looked at the history of diesel railcars.

The twelve boards are reproduced here. I've kept the originally layout, which means they are best viewed on a regular computer screen rather than a mobile device. I've also left the text as written, so some items are now out of date.

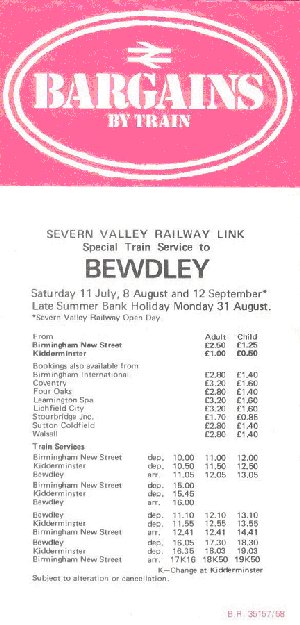

There is also an additional board looking at DMU special services between Kidderminster & Bewdley 1979 - 1983. Written by Paul Jackson, printing problems meant it couldn't be displayed at the event.

Board One

|

IntroductionRailcar50 is all about first generation DMUs. What is a first generation DMU? What are they so special to warrant this event? These twelve boards answers this, telling their fifty-year history, where they came from, and their part in the evolution of our railway vehicles to the trains of today. Most importantly we hope to show you how you can play a part in keeping a piece of that story alive. Railcar50 has two main aims — access and education. We are providing better access to these vehicles by bringing a selection here for you to enjoy, to see the variety of different types there were, to be able to experience travelling on some, and provide you with information where you can see further examples. We hope that at the end of your visit you will know more about railcars than before, and learn about some of the hard work, dedication and cost that is involved in restoring and maintaining the preserved examples. All the owning groups have allowed us to bring and use their vehicles free of charge. Please support their work. Without them we wouldn't be here. |

Railcars, diesel multiple unit (DMU), diesel train are some of the various names (many derogatory!) to describe the same things - self-propelled, diesel powered trains. A pair of horizontal diesel engines is suspended under the floor driving the inner wheels at each end. Transmission is through either a four speed gearbox (mechanical units) or a torque convertor (hydraulic units). Further technical information is available in the 'Diesel instruction Coach'. |

||

|

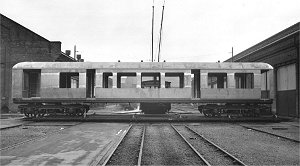

Below: One of the vehicles that started it all. A Derby Lightweight vehicle ready for delivery to the West Riding of Yorkshire in 1954. |

||||

|

Top Right: Now that Railcars have all but gone from the national network, there has been much greater interest in them, and they seem to fit in far better in the preservation scene. Right: Tasks in DMU restoration can be mundane, but very satisfying. Over the years this vehicle has had many coats of paint, and they were starting to peal off and crack and craze. So on this vehicle it all had to be removed. |

|

||

Board Two

|

Pre-DMU daysSelf-propelled passenger carrying vehicles can be found dating back to the 1840s, when experiments were done involving the rearward extension of loco frames and the addition of carrying axles. They were for staff transport, although revenue earning use was hinted at. Ireland is recorded as being the first to carry passenger, as in 1873 the Great Southern & Western Railway produced four loco-carriage long-framed vehicles. They had 14 seats! Just after the turn of the century the favoured version was a four-coupled (sometimes six) tank loco, sweated onto a compartmented carriage body by either attaching the boiler and cab, or by enclosing the 'loco' within the carriage body. Both approaches were adopted for articulated and rigid under-frame designs. More than twenty Railways produced almost 200 such vehicles between 1902 and 1911 — with the GWR having over half. These remained in operation until 1935, with some being rebuilt to auto-trailers for use with push-pull equipped panniers and 2-6-2T locos and some survived right through into nationalisation. Some still operate in preservation. |

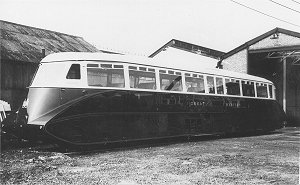

Below: The first of the GWR railcars was built by AEC at Southall (underframe) and Park Royal coachbuilders (body).

Below: No. 33 (nearest) was rebuilt with a gangway after No.37 was destroyed by fire, to run with No.38. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

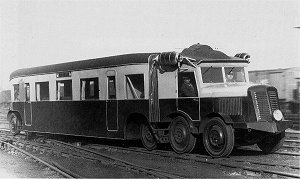

Right: It may not be surprising to learn that a vehicle sponsored by the Michelin Tyre Company ran on rubber tyres. This vehicle, built in 1932 was a road-coach-like vehicle, with an articulated body carried on a six and four wheel 'bogies'. It was extremely light (only 5 tons) and well appointed internally and seems not to have survived trial operations between Bletchley and Oxford. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Internal combustion railcars also appeared about 1900, using petrol or diesel engines, and electric or mechanical transmissions, and these, with a variety of other steam types, didn't have any overwhelming success, until the GWR diesel cars of the '30s/'40s. In 1933, the GWR, AEC and Park Royal got together to design a railcar based around then current bus technology. AEC had trailed a flanged-wheeled road bus on the GWR with reasonable success but an overall design concept more favourable to rail operation was required. So, a double ended railcar design evolved, with a single 120 h.p. diesel engine. In a very similar configuration to the AEC Q bus chassis of the time, the engine was mounted vertically outside the frames, and drove via a fluid flywheel and four-speed epicyclic gearbox to final drives on both axle boxes of the same bogie. But the most striking feature was the Park Royal bodywork. Highly stylised and very much in line with the advanced design thinking of the day. Under-powered, and devoid of draw and buffing gear, this prototype was rapidly followed by successive batches each with enhanced design features. By 1942 the fleet had expanded by another 37 vehicles, 17 with bodies by Gloucester R C & W, and 20 in-house at Swindon. The evolvement of the fleet shows a technical development towards the railcars that BR would build, and the small multi-purpose GWR fleet shows surprising similarities to the huge selection that BR would have! |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Right: The LMS produced a 3-car articulated vehicle in 1938, one of the most striking diesel trains this country has seen. Unfortunately, only one set was ever built. The advent of WWII killed it off very quickly (it was converted to an overhead line maintenance train). The power train specification of two 125 h.p. Leyland engines with Lysholm-Smith torque converter transmissions and reversing final drives on axles, controlled using 24V EP controls could read the same for the first batch of Derby Lightweights in 1954 |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Board Three

|

Early Thinking, PlansRailcars had been in use on the continent for several years before the Railway Executive took a serious look at how effective a 'diesel train' would be in this country. The resulting report saw £500,000 authorised for multiple unit trains on the 11th September 1952. It was later determined that the area to 'trial' these on was the West Riding of Yorkshire. Many other proposed schemes were discussed, for example in December 1952, it was agreed that in order to improve the suburban service in & out of Kings Cross, a scheme should be prepared urgently to employ a number of Multiple Unit trains. That 'urgent' scheme fell by the way side a bit while others took priority. With the first vehicles still not anywhere near ready, in June '53 the potential for the use of these vehicles must have been apparent as an additional £120,000 was authorised to now provide 21 two-car sets in total. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

All regions were asked to look at how they could utilise railcars, and as an example in July '53 the London Midland Region had under consideration the: Watford - St. Albans; West Cumberland; Manchester - Buxton; Bury - Bacup; Manchester - Liverpool / CLC lines and experimental City - City services. Regarding the City - City services, it was quoted "The traffic officers, in conjunction with the ER traffic officers, are investigating the possibility of experimental services with diesel units between Ipswich, Norwich, Peterborough, Leicester & Birmingham." |

A "Committee on Lightweight Trains" was established, to progress the plans, containing names such as RA Riddles and RC Bond. In August 1953 a scheme for West Cumberland was approved, involving 13 2-car sets at cost of £331,500, although the priority of schemes was considered and West Cumberland received the additional 13 sets already ordered. The Glasgow-Edinburgh line was an obvious candidate for modernisation. It was Scotland's premier route, but the short high speed line (47 miles) proved tiresome to the current motive power. After a lot of forethought approval was given in Oct. 53 for £645,000 on new vehicles for complete dieselisation of the Queen Street - Waverley route, and partial dieselisation of the Central - Princes Street route. The trade was asked to quote for these, although soon after it was decided to give Swindon the task of these, along with sets for Birmingham - Swansea line which had been proposed but not yet approved. The specifications outlined were: City to city (Edinburgh - Glasgow) For Birmingham - Swansea |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

It took some time before the Birmingham - Swansea sets were properly approved, but in the end the same type was built for both lines. The plans for the Edinburgh - Glasgow sets also evolved considerably by the time they were build & delivered, as in the end only Queen St - Waverley got some from this build, and they now nominally 6-car sets but could work as 3 or 9 car sets. They didn't get gangways throughout, but uniquely there were two cab designs, a full width 'leading' cab and a gangwayed 'intermediate' cab. Lincolnshire were next to be allocated units, getting the displaced 13 sets from the West Cumberland announcement in November '53. As the number of schemes being approved increased, with 13 sets authorised for East Anglia, and the 'trade' were asked to quote for other schemes, due to the capacity of railway shops. The same month the purchase of trial ACV vehicles was approved for use on the Watford - St. Albans services (at a cost of £36,300). The final authorised scheme of 1953 was for 20 vehicles for the Newcastle - Middlesborough line at a cost of £255,000. When considering schemes there were many factors to be considered, other than just the logistics and cost of building the vehicles. What stock would they replace? What would the cost element be, not just in purchasing the vehicles themselves but also in the infrastructure required to operate them? What would the effect be on operating /maintenance staff, and training? And what effect would they have on passenger numbers, given the more attractive timetable they could operate, and shiny new trains? |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Board Four

|

The Early TypesIn 1954 the first vehicles emerged from Derby C&W Works, delayed through problems such as design and suppliers. After a press run, the reaction to the units was mixed. They were immediately praised for their attractive design, the unobstructive view of the line ahead / behind, and for the provision of luggage racks and toilets. However they were also criticised for the lack of compartments, the bus type seats and the lack of arm rests in the 3rd class areas, and the height of the seats and head rests, which spoilt the view. The public / press would apparently have preferred "reversible" seating as found on trams, which they suggested as an alternative to having to sitting backwards. (The official reply was that this type of seating was considered, but would have required additional leg room, and a reduction in the number of seats by 15%. This did appear on some later units.) The vehicles were also criticised for being contrary to the "standardisation" policy at the time, particularly as the SR EMUs being built were based on the standard MkIs, and because buckeye couplings weren't fitted. On Saturday 12th June 1954 five brand new 2-car sets in immaculate condition were lined up at Bradford's Hammerton Street depot, ready to commence operations on the Monday. The first passenger carrying DMU to run in this country pulled out of Leeds Central at 8:06am on the 14th of June 1954. The benefits of these sets obviously got the powers that be excited, as in Dec. '54, the construction of 858 power cars and 550 trailer cars was authorised, at a cost of £17,570,000. These were unallocated to schemes, but were up for grabs by any region that could prove their usefulness. |

|||

|

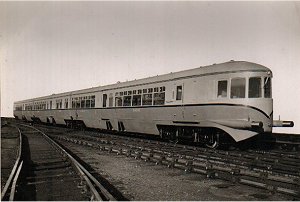

"Lightweights" The 79xxx vehicles from Derby are commonly knows as 'Derby Lightweights', and the 79xxx cars from Met-Camm are also known as the 'Met-Camm Lightweights'. The Derby cars were built from aluminium, but the Met-Camm vehicles were steel framed / panelled, with the exception of the centre roof panels, exactly the same as the 5xxxx series cars. They were branded 'lightweights' as at the time of introduction, 'lightweight diesel trains' was a common term to describe the new railcars in general, as they were much lighter that the coaching stock being built at the time. |

||||

|

Left: The first private built units were from Metropolitan-Cammel, in Aug. '55, and were sets for the Bury - Bacup line and East Anglia. These were able to be coupled to the Derby sets, but not later vehicles, and could be differentiated by the electrical sockets just under the cab windows. The Met-Camm design was one of the most successful to be built. |

|||

|

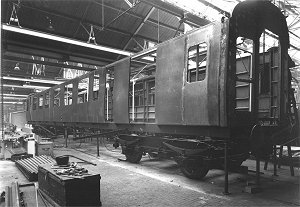

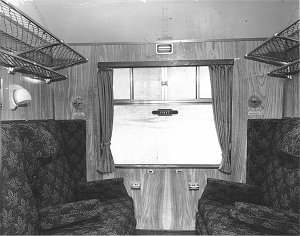

Left: Swindon C&W Works experienced more than it's share of delays, the first vehicles emerging some three years after they were authorised. The Inter-City stock was more akin to coaching stock. This is an intermediate driving car - the apertures are cut out on the end for the cab windows / indicator boxes. There is a temporary trussing fitted to the underframe to support it until the body / roof is added. They were separately jig built. Right: Believe it or not, this is inside a DMU car! The first class seating on the Swindon Inter-City sets was in compartments. |

|

||

Board Five

|

The Modernisation PlanThe famed 'Modernisation Plan' of 1955 stated that there would be ultimately be over four thousand vehicles introduced in the elimination of steam, although a later review cut this number back. Workshop capacity meant that the 'trade' was increasingly used, sometimes to their own designs, sometimes to BR designs. It was a common situation to that with to locos, in that vehicles had to be ordered in large numbers before they were properly trialed, with the resulting problems that that brought. The vehicle's control system had by this time evolved into a new system, and they were given 'coupling codes' to differentiate them, with most vehicles from 1956 on having the 'Blue Square' type. The developing technology that allowed railcars to be the success they were, was borrowed from road vehicles. The increase in road usage meant that the savings that the railcars brought to services wasn't always enough, and many lines were closed in the late '60s. The resulting surplus in units say some of the earlier, with their non-standard coupling codes, withdrawn. All the vehicles built can be classified as one of the following: Inter-City - long underframe (64 ft 6 in) based on loco-hauled vehicle design

|

Above: The Gloucester Railway Carriage & Wagon Company built forty of these two-car power-trailer sets, later Class 100, for the Scottish & London Midland Regions. First introduced in 1957, they lasted until 1988. One power car and three trailer cars remain in preservation.

Above: On the right is seen a unit built by Cravens Ltd of Sheffield. The company produced 405 vehicles, in four variations, all based on the same bodyshell. The were first introduced in 1956 and lasted until 1988. Three vehicles survive on preservation. One the left is one of British Railways experiments. A pair of the Derby Lightweight vehicles were fitted with traction motors and a large number of batteries to power them. Sponsored by the local hydro-electric board, this battery multiple unit was tested on the Aberdeen - Ballater line. While the vehicles were not unsuccessful, no more were built as such. After the line closed they were taken on by BR's research department for testing automatic train control, which allowed them to survive into the preservation era. They are in store awaiting a stretch of the Ballater line to reopen once more. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Vehicles built (not including railbuses)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Below: After building the 'Derby Lightweights, which were all aluminium based, Derby built these steel vehicles, which were also the first vehicles to be built on the longer 64ft underframe. The cab was also redesigned, and used on all vehicles built by the works after that. Originally having 150hp engines, they were found not to be powerful enough for the heavier (steel / longer) vehicles. By the time the last vehicles were built a more powerful 238hp engine was fitted, and retrospectively to the rest. Forty-nine sets were built for services around Lincolnshire, Humberside and the East Midlands, later classified as Class 114s, and one other as a test bed for a Rolls-Royce engine fitted with hydraulic transmission. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Right: 1957 saw the first 'high density' or 'suburban' design. Intended for use on commuter services where there were large numbers of passengers, there were doors fitted to each seating bay to allow fast loading / unloading. Such usage normally meant short journeys, so there was no through access between vehicles. The introduction of paytrains however meant that gangways were added later. This version was built for the Western Region mainly for services from Birmingham and South Wales, working many of the valley services. Later they were used around most of the country. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

Board Six

|

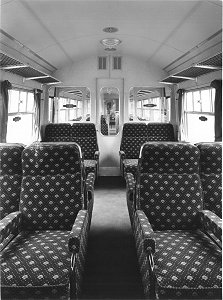

Service improvementsThe new railcars made a big impact to public services, and the railway was proud of the fact and was keen to relay this in its literature. The passenger accommodation, mainly with laminate (a new material then) or vinyl coverings, which gave a clean feel as well as in reality being much cleaner without all the soot and ash that goes with steam locos. The bus type seats gave them a much more roomier feel, and aiding passengers visibility of the passing scenery, and of their biggest selling point, the view of the line ahead. For the first time many people could see what the driver sees, watch how he responds to signals, and be no doubt Be curious as to what some of the controls indicators actually meant. And why they had a 'steering wheel'! (actually the parking brake). The operational advantages of the units: quick turnarounds; no coaling or watering; quick start ups; and reduced crews allowed the timetables to be transformed. Regular interval timetables were introduced for the first time in many cases, journey times reduced, and longer operating periods - some lines now had earlier / later trains and the introduction of Sunday services.

|

First class sections had more comfortable armchair seating, curtains and often carpet rather than lino. |

||

|

Below: A selection of promotional literature. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Board Seven

Above: Derby Works returned to aluminium vehicles again, producing an updated version of their Lightweights. The same body was used, but with the now standard Derby cab in steel. Underneath the mechanics and control system was the standard blue square system, and the interior little changed other than more basic seats. As with the earlier Lightweights, these were produced in 2, 3 & 4-car sets, and 333 vehicles were produced. Being aluminium, and never having had blue asbestos insulation, they have proved very popular in preservation, with over 50 vehicles saved.

Above: In BR days the WR continued to make use of the GWR railcars, although most of these were phased out with the introduction of single car vehicles, with a cab at both ends. Derby was the first to produce these, two 'Lighweight' versions being built to trial on the Buckingham - Banbury line in '56. In 1958 GRCW built 19 based on Derby's high density design, and in 1960 Pressed Steel built a further 16 (as pictured). The later two versions were also supplied with a few non-powered trailer cars for addition in busier times. There was no through access because of the cab, but this was in line with other WR sets. |

A Wide Variety of VehiclesHere we look at some other types of vehicles built. There were others, that we don't have space for!

Above: The Park Royal company were responsible for twenty 2-car sets for the LMR. As a rule, first class sections were behind the driver on the trailer cars. Driving trailers are strangely quiet, being remote from the power cars. Although still bus-types seats, there is still a more luxurious feel to it, with the curtains and carpet, armrests. The seat material is one of the most patterned to be used in DMUs, and was no doubt also found on buses of the period.

Above: BR's design panel had an influence in almost all DMU designs, although this was mainly restricted to interior finishings. Latterly their involvement increased to include exteriors. Swindon's sets had been particularly criticised for their bland cabs, so when sets were being designed for a 'Trans-Pennine' service they involved an independent industrial design expert to help produce what is now regarded as one of the best designs. It was produced as a one-piece glassfibre moulding. The Trans-Pennine sets, as they became known, had two 'intermediate' power cars without cabs in the six vehicle formation, ensuring there was enough power for the hilly routes they were to operate. |

Above: This is Swindon's Cross-Country type. The body and cab are based on their earlier Inter-City type, and the lining and 'whiskers' do little to hide the basic utilitarian look. As they were designed for slightly longer journeys, most of the Cross-Country vehicles had a mini-buffet in the centre car. These were built mainly for the Western Region, with a few for Scotland, although many ended up in the Midlands latterly.

Above: Swindon Works couldn't produce enough Cross-Country sets quick enough and so GRCW were asked to build some, and curiously they emerged with the Swindon body but a Derby cab! In this view there is coach inserted to give extra capacity. The WR converted a few of these for this purpose, painting them into DMU colours (even with blue squares) and fitting them with jumpers and vacuum release pipe. The coach made the standard 3-car set into a 4-car. The 3-car set attached at the rear is a Swindon Cross-Country set, the easy way to differentiate in views such as this is that the Swindon type had less roof ventilators!

Above: Derby Works produced two batches of almost identical 4-car sets back to back, the first for services out of St Pancras, and the second for services out of Marylebone. The St. Pancras sets used hydraulic transmission, and one is seen on the right of the picture. The Derby cab has evolved from the 2-digit route indicator as seen on the aluminium bodied car on the left, to the newly introduced 4-digit type which was moved to the roof. Interestingly none of the 2-digit versions were updated to carry the new codes. Many more high density vehicles were also produced for the Western Region, built by Pressed Steel and GRCW to the Derby design. |

|

Right: Parcels car. It was something the GWR had already done with their railcars. Cravens built three vehicles, although they had restricted use, being given 'yellow diamond' coded control equipment two years after 'blue square' had become the standard. This is because they were intended for use in areas operated by yellow diamond vehicles. GRCW built ten vehicles for the WR and LMR, the WR wanting gangways fitted, the LMR didn't. They had more powerful engines fitted, to allow them to haul a tail load as in this view. In later years, numerous passenger vehicles replaced by modern stock were converted for newspaper / parcels carrying. |

|

Board Eight

|

Refurbishment and ReplacementWhile DMUs made a considerable improvement over the stock that they replaced, after a period more modern rolling stock showed that DMU interiors were somewhat functional. Despite being designed for a 20-25 yearlife span, there were no units in development that could replace them, nor was the funding available for mass replacement. The DMUs were still technically sound, and so a refurbishment scheme was embarked upon in the mid-'70s to provide more attractive travelling conditions. One Met-Camm set was first treated, each of the three vehicles were treated differently and the unit went on a three month tour of the country in which Passenger Transport Executives and other bodies with interests could inspect and comment on the design. About 1,800 were eventually treated, after deciding on the life expectancy of each class. The improvements included fluorescent lighting, new upholstery and carpeting, the fitting of vinyl to wall panels and the now infamous orange vestibules. There was also work done on engine mountings, to help improve vibration problems, and various other mechanical improvements such as revised exhaust systems. Eventually a new bread of units appeared, and began to replace the first generation units. But these were never built in the same numbers, and have had many problems that has meant that it has taken almost 20 years to phase in the new breed, and there still remains a single vehicle still in passenger use on the network. This saw the units survive into the sectorisation /privatisation era, with the multitude of different liveries that it brought!

|

Above: In the protoype refurbishment one car was given new seating, 2nd class being Class 313 EMU style, and 1st class (pictured) being Mk2f/3 'Inter-City 70' adjustable seats.

Above: Refurbished cars were identified by a new livery. However it proved impossible to stay looking clean and smart, so they were changed to blue / grey, which had otherwise been retained for inter-city / cross-country stock, unrefurbished cars nominally staying plain blue. |

||||

|

Below: The later years in particular often saw sets of mixed up types. In Network South East livery is a unit formed of BRCW Class 104, Met-Camm Class 101 and Pressed Steel Class 117 vehicles. |

||||||

|

|

|

||||

Board Nine

|

Preservation - the early daysAlthough the earliest first generation vehicles to enter preservation were some of the 4-wheeled railbuses when they phased out, but early withdrawals of some DMUs allowed preserved lines to buy them and use them on the same basis that BR did - they were cheap and easy to operate. The first line to make use of them was the North Yorkshire Moors Railway, marketed as operating a "National Park Scenic Cruise", and ideal during dry periods in the National Park when there was a steam ban. The West Somerset was another railway that made use of them early on, having Park Royal & Cravens sets, and later buying the NYMR GRCW sets. While these sets were bought for operational benefit, to be disposed off when worn out, the first set bought for preservation on historical merit was one of the Swindon built Inter-City sets from Scotland. Despite being bought in 1983 the unit has had kept a very low profile, as it was kept in full working order on a non-operational railway for ten years, then moved to an operational railway but immediately asbestos stripped, and is still being rebuilt after this. Asbestos has been a major downfall in DMU preservation, limpet blue asbestos was frequently used in walls, ceilings and floors, and many early units preserved were sold still containing this. BR did strip many units with longer life expectancies, but some types were not. Many types are now lost forever, as when regulations tightened asbestos stripping was compulsory, making the cost prohibitive to preservationists. The Swindon types suffered the worst, with only five vehicles remaining from the hundreds built. Thankfully as withdrawals stepped up interest in them grew, meaning that around 250 vehicles have now been preserved, with the Class 108 aluminium vehicles being a favourite, and the Class 101s and 117s in large numbers perhaps due to the fact that as the demand for these rose these were the only vehicles available. Many types have survived only because some went into departmental use, such as the surviving Derby Lightweights, or bought as 'disposable units' in early preservation days. |

Above: The North Yorkshire Moors Railway bought two GRCW twin sets, seen here entering Goathland.

Above: Four of the five German railbuses were saved, two on the North Norfolk Railway and two on the Keighley & Worth Valley Railway, one of which was painted into their own house livery. Below: There is already a growing list of vehicle that were once 'preserved' but have now been cut up. This AC Cars railbus body is seen on the Strathspey Railway. The lack of the chassis with all the mechanics and running gear, and the blue asbestos insulation, meant it was disposed of. |

||

|

Below left: The battery multiple unit is an example of a unit that only survived onto the preservation era as it went into departmental use. A normal twin Derby Lightweight set also survives, which had been in use as the ultrasonic test train, and one of the single cars from the Buckingham - Banbury line, which had become Test Car Iris. Below centre: Claimed to be the first DMU vehicle preserved, Gloucester DTC 56301 is seen here on the Chasewater Railway, and used with a steam loco in the fashion of an auto-coach. |

||||

|

|

|

||

Board Ten

|

Preservation - the HLF ProjectsWhen the National Lottery was introduced in 1994 they formed bodies to handle payments to good causes, under several topics. One of these was the Heritage Lottery Fund. In general awards are assessed on their historical merit, and the benefits that the grant will bring to education and access. Three awards have now been made towards the restoration of DMUs, all of which had been left as empty shells following asbestos stripping: £180,000 for the Class 126 on the Bo'ness & Kinneil Railway, £129,000 for the Wickham unit on the Llangollen Railway, and £49,000 towards the Derby Lightweight power car 79018. They have also granted £49,000 for staging Railcar50. The Class 126 grant covered the contract restoration of the two power cars, and the materials for the restoration of two trailer cars which were to be done by volunteers. Unfortunately the contractor ran into many problems with residual blue asbestos, and also underestimated much of the work, which stalled the work. A recovery plan is being discussed with the HLF. The volunteers have almost completed the first trailer car, which should be on display here, and much material for the second trailer has been prepared. Almost all the Wickham work was done under contract at the Midland Railway Centre, as was the Derby Lightweight car, also seen here. Keep buying those lottery tickets. It's also benefiting DMUs! |

Above: Derby Lightweight power car arrived at the Midland Railway Centre as a stripped out shell, and was also missing many mechanical parts that had been taken to keep Test Car Iris running. Below: A view that has already been photographed thousands of times. The original 'yellow diamond' control system has been retained, so the vehicle cannot be used until the trailer car is complete.

|

||

|

Right: The interior of the Lightweight power car on arrival. Many parts had been acquired from Class 108 vehicles which were similar, and the volunteers started to assemble the interior with these. |

|

||

|

Left: Asbestos stripping left this Swindon Inter-City car as an empty shell. Some interior items were returned but a lot of items been contaminated and destroyed, or not in a fit state to re-use. The extent of the bodyside corrosion also now became apparent, a problem that couldn't previously be addressed as it would have exposed asbestos. The volunteers were faced with a mammoth task, particularly as they had four vehicles in this condition. |

||||

|

Left: The same vehicle during work at the contractors. All of the lower bodysides and a substantial amount of framework had been replaced, new partitions built, new floor laid, new ceiling timbers made and insulation fitted. |

|

||

|

Right: The HLF grant allowed new materials to the original specification to be used, and the vehicle has been restored referencing the original 'build specification' used when it was new. At also speeded up the restoration, what would have taken the volunteers at least ten years to reach a much lower standard of finish, has been completed in six months. |

||||

Board Eleven

|

Preservation NowGrants from the Heritage Lottery Fund are not essential to achieve quality restorations, as some of the vehicles here will demonstrate. Volunteers are a crucial element in DMU preservation. And what satisfaction do we get out of DMU preservation? It includes elements of both the other main preservation options - locos or coaches. You can get your hand dirty crawling about underneath on all the mechanical work - it's all very straightforward technology, easy to pick up but it can still get you thinking. The electrics are relatively straightforward, and we've got air and vacuum systems to play with. We can go to town on the painting, and make them much prettier than a loco. And there are loads of skills to be learned and used inside. Fancy a bit of lino laying, or fitting some sliding doors so they run freely? A bit of varnishing, fitting some windows, or cleaning some aluminium mouldings? What about recovering some seats, or cutting and glueing some formica panels? The joy is that we have our own self-contained train. We have the public come inside our work, travel on our work. Their happy faces are what makes it all worthwhile. To find out more about becoming involved, speak to any of the volunteers here this weekend, or check the website at www.railcar50.co.uk. Help keep the railcar story alive!

All the hard work pays off. The volunteers spent ten years restoring this vehicle, and must be very proud of it. |

Fancy a bit of welding? This Gloucester cab will need complete replacement of the platework, and no doubt much of the framework behind, where the lines of rust bubbles are.

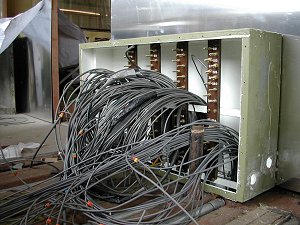

Any good with wires? Each power car has about two miles of wiring. |

||

Good paint finishes are determined by the preparation. Cabs are particularly awkward to sand, and a lot of it has to be done by hand. Here Derek Miles get's stuck into one of the SVR vehicles. |

||||

Board Twelve

|

We wish to thank to all the photographers that have allowed us to use their pictures for the event. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Additional Board

|

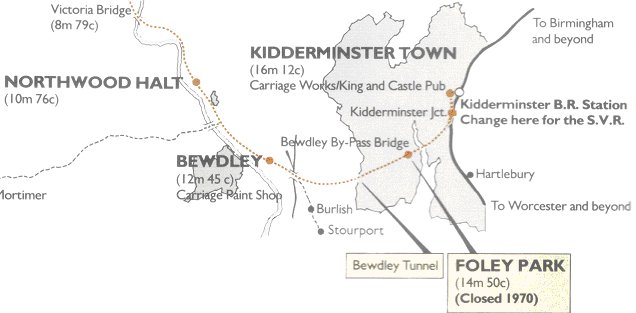

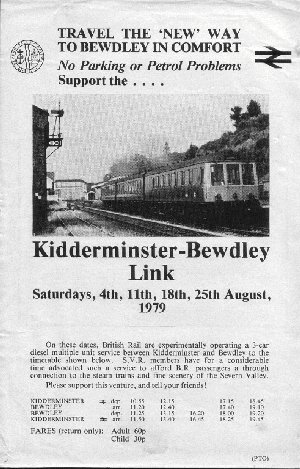

DMU special service between Kidderminster & Bewdley 1979 - 1983 (or how British Rail DMU's filled an important gap)By Paul Jackson After the regular BR Kidderminster / Bewdley / Stourport passenger service had ceased in January 1970 the line between Foley Park and Kidderminster remained open to freight traffic, serving the sugar factory. |

||

|

The SVR section of line to Foley Park remained intact, directly connected to the BR freight line from Kidderminster and thus permitted through train movements from one system to the other. The physical barrier was a pair of catch points to prevent illegal train movements from one section to the other. On the BR DMU special service days these points were 'clipped' and hand signalled by a BR signal man residing in a solitary positioned brake van in a siding adjacent to the single running line. This was also the era when SVR passenger trains occasionally ventured along the same line, albeit from the Bewdley direction and going through the tunnel to the Foley Park boundary limit. Normally only happened during special events or galas, often 'topped and tailed' by steam locomotives due to a lack of run around facility. |

||

|

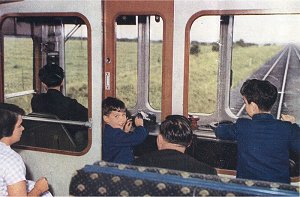

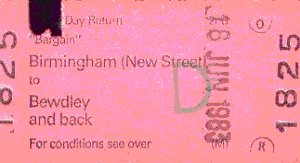

Initially, the special days only DMU service into Bewdley was introduced as an experimental short shuttle from Kidderminster commencing during a 1979 Bank Holiday. Proving successful the natural progression was to eventually extend the operation through to Birmingham New Street by the then termed BR 'Provincial' sector. Services eventually became linked to steam railway gala events due to the DMUs suitability to efficiently transport large masses of people. Running dates were advertised in the monthly West Midlands charter programme leaflets. Trains were driven by a BR driver and accompanied by a SVR pilot man who joined the set at Kidderminster. Arrival at Bewdley was normally into platform one. The set then ran onto Wribbenhall viaduct to reverse into the island platform to pick up passengers for the return to BR metals. It provided a useful cross platform interchange for steam services arriving from Bridgnorth. |

|

||

|

|

||

|

Eventually the business proved to be very popular and ticket sales were extended to include many stations within the West Midlands. Often the first DMU train of the morning out of New Street was strengthened with a further 3 cars by local BR staff due to heavy seating demand - a practice almost unheard of today. |

|

After 1983 freight traffic ceased to the sugar factory and the DMU link was stopped after the September 1983 Autumn gala. The Severn Valley Railway then acquired the remainder of the route, and by 30th July 1984 the SVR had extended steam operations into Kidderminster thereby ending the need for a DMU connecting service. |

|